An often-used adage over the past year – albeit mostly in reference to the US Federal Reserve – is that central banks will “raise interest rates until something breaks”. There are signs that we may be reaching that point as sentiment across several advanced economy central banks seems to have shifted in recent weeks, beginning first with the Bank of England’s intervention in the UK gilts market;[1] while the European Central Bank (ECB) appears to be giving more weight to recession risks and widening bond spreads; and the Bank of Canada (BoC), despite noting that the economy is operating with excess demand and experiencing sharp price rises, decided to slow the pace of rate hikes to 50 basis points at its most recent meeting. The BoC’s latest increase brings the policy rate in Canada to 4.25%, with officials now highlighting the risks of over-tightening even as real rates remain steeply negative.[2]

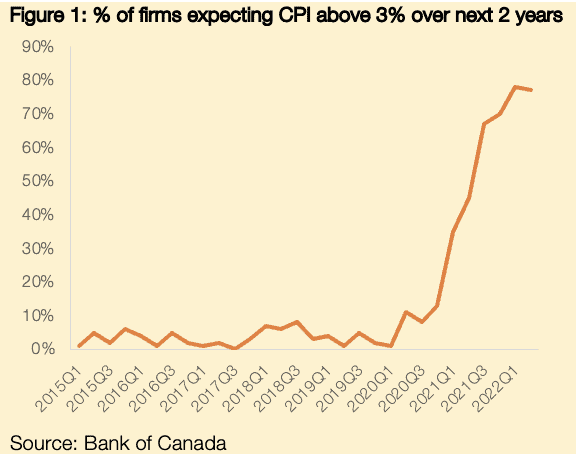

According to orthodoxy, one would expect the BoC’s shift to have been prompted by either: 1) progress in bringing down inflation and inflation expectations; or 2) signs that economic activity is slowing towards levels that are more in line with fundamentals, thus prompting a moderation in inflation going forward. Concerning the former, there is little evidence that inflation has slowed significantly: headline inflation came in at 6.9% y-o-y in October, only 1 percentage point lower than the peak reached over the summer. Furthermore, much of the recent progress reflects weaker commodity prices, whereas ‘stickier’ inflation components continue to grow. Indeed, core inflation has remained above 5% y-o-y in recent months and shows few signs of moderating quickly. No progress has been made in reining-in inflation expectations either, with three-quarters of firms expecting CPI to remain above 3% over the next two years (Figure 1).

In terms of the BoC using monetary policy to slow growth and rebalance supply and demand, estimates of Canada’s output gap remain positive at between 0.25% and 1.25%, suggesting that tighter monetary policy and further slowdown is needed.[3] Nonetheless, while progress in the aggregate appears limited, there are initial signs that rising interest rates are beginning to slow the economy, with analysts increasingly anticipating a mild recession in 2023. Slowing economic activity is especially noticeable in areas that are more sensitive to interest rates: in the construction sector, for example, economic activity has contracted in the past 5 consecutive months as rising mortgage rates reduce the demand for homes, especially in overvalued locations; while related activities (e.g., mortgage origination) are likely to have also fallen in tandem.[4]

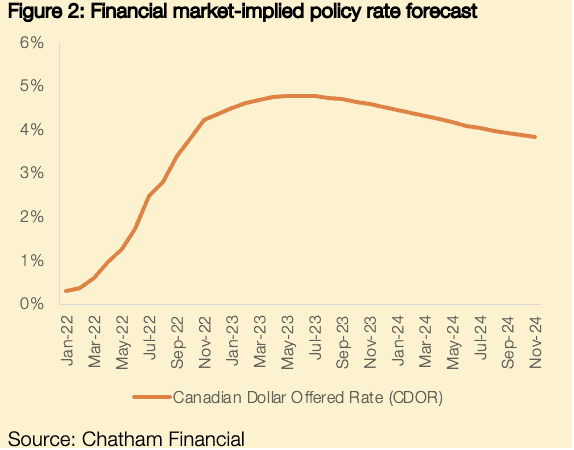

In view of inflation remaining markedly above-target, the BoC’s shift in rhetoric has confounded financial markets’ earlier expectations for continued aggressive rate hikes going forward, with focus now shifting towards the ‘terminal rate’ that will be reached during this tightening cycle. In sum, financial markets’ focus has shifted from the ‘journey’ (i.e., the pace of rate increases) to the ‘destination’ (i.e., the level that rates will ultimately reach). Currently, financial markets expect interest rates to peak at around 4.75% in Canada in early 2023, before declining very gradually thereafter (Figure 2). These projections are subject to change given that they are based on financial market perceptions. Nonetheless, they indicate that an end of the BoC’s tightening cycle hikes is coming into view.

The key question at this stage is, ‘Will a policy rate of 4.75% will be enough to quell inflationary pressures and sustainably bring core CPI down to the BoC’s 2% target?’.[5] The BoC clearly expects that this is the case, noting that it takes time for the effects of higher interest rates to fully disperse throughout the economy.[6] It appears, then, that we have entered a wait-and-see period as the BoC’s searches for answers to this question.

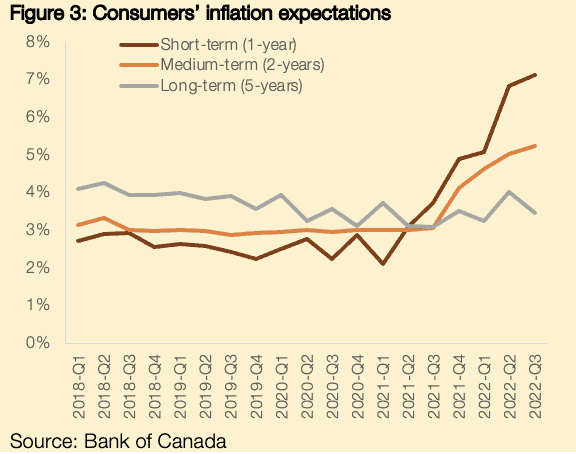

At Ballad, our response is skeptical given that we see significant risks surrounding a more moderate approach to monetary policy, principal among which is a de-anchoring of inflation expectations across consumers and businesses. Although longer-term expectations remain stable for now, consumers’ short- and medium-term inflation expectations have already risen sharply (Figure 3). A new round of inflationary pressures – caused by, for example, a re-acceleration in energy prices – would likely cause a reassessment of these longer-term expectations, as well as prompting more widespread demands from workers for multi-year pay increases to cope with cost-of-living increases. The emergence of such a wage-price spiral would make the BoC’s task of reining-in inflation even more difficult.[7]

Given the macroeconomic backdrop and the considerable risks of prematurely slowing the pace of interest rate hikes, it is reasonable to ask why the BoC has seemingly changed course. One possible answer lies in the vulnerabilities and fragilities present in the Canadian economy, including its limited capacity to tolerate higher interest rates from here. As noted earlier, signs of slowing economic activity are much more evident in interest-rate sensitive sectors such as construction and related financial services. Essentially, households that are already heavily levered are unable to take on more debts for new home purchases or other big- ticket items, especially as interest rates continue to rise. The amount of credit extended to Canadian households reached a new peak of $2.7 trillion in the first quarter of 2022, equal to 106% of Canada’s annual GDP and spurring a housing market boom in which prices have more than tripled since the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, whereas many other advanced economies saw reductions in household debt following the crisis, the Canadian household sector has accumulated debt rapidly to become one of the most highly leveraged in the world.[8]

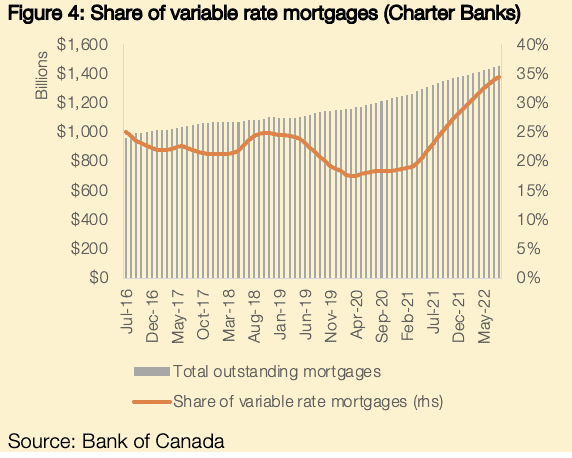

What does this debt build-up mean in a new paradigm in which interest rates are no longer zero? Firstly, we split the mortgage market into its component parts: 1) variable rate mortgages which see their interest rates fluctuate in line with BoC policy; and 2) fixed rate mortgages, often for a period of 5 years. New mortgage issuance has shifted towards variable rates in recent years, particularly as the interest rate spread to fixed rates widened and lenders offered discounts to attract new borrowers into the market. For example, those who took out a mortgage at a variable interest rate between April 2021 and March 2022 would have saved between 50 and 150 basis points in interest over a 5-year fixed rate mortgage.[9] These incentives resulted in the share of new mortgages that have a variable rate reaching a high of 60% in recent quarters, while the share of all outstanding mortgages that have a variable rate now stands at 35%.[10]

The rapid pace of rate increases is already affecting this segment of borrowers, albeit not necessarily through higher monthly payments. Rather, most variable-rate mortgage holders have fixed monthly payments. This means that rising interest rates result in less of their payment going towards the principal balance, and more is going to pay off the interest only. Some borrowers are even facing the prospect of negative amortization, meaning that their payments are not even sufficient to repay the interest. In these cases, the outstanding balance on the mortgage is growing over time. Recent forecasts from RBC expect that some 80,000 of its variable-rate clients will reach this scenario by the end of 2022.

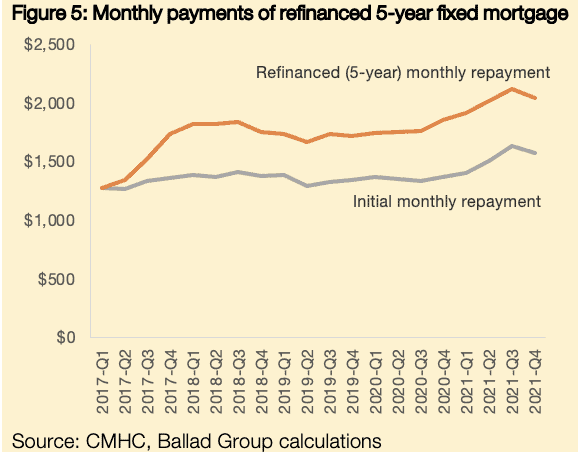

For fixed term borrowers, meanwhile, many will see their interest rates reset at a higher level when they renew their mortgages over the coming years. Using Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) data regarding the average new mortgage value from 2017-Q1 onwards, we have set out the implications of rising rates on the monthly repayment schedule of these borrowers.[11] Using financial markets’ baseline forecast of the BoC’s policy rate (see Figure 1), we find that the average monthly payment of borrowers who took out their first mortgage in the past five years will increase by 27% over the period 2022-2026 (Figure 5). We have checked the sensitivity of our estimates to higher interest rates than current baseline forecasts: a 100-basis point increase in mortgage rates above our forecast results in a 36% increase in monthly payments, while a 200-basis point increase in mortgage rates above our forecast leads to a 46% increase in monthly payments. No matter what way you look at it, it is a certainty that Canadian households are about to experience significant increases in debt servicing costs.

Rising mortgage payments coincide with a downturn in the housing market that looks set to get worse before it gets better. Prices have already fallen sharply in only a few months in locations such as Hamilton (-12.6%), Toronto (-8.5%), Victoria (-6.7%), and Vancouver (-6.6%).[12] Bringing house prices down to pre-pandemic levels from here would require an additional decline of at least 25% in many areas. What appears to be materializing, then, is a market in which a not-insignificant number of homeowners – especially those that bought during the later phases of the pandemic or with variable mortgages that have hit their ‘trigger rates’ – are left with a loan that exceeds the value of their home. Fortunately, delinquencies and mortgage arrears do not point to any signs of distress at this stage, but this is a metric we’ll be keeping a close eye on, especially if they start to weigh on the financial sector. With these concurrent headwinds hitting the housing market and existing borrowers, it is little wonder that the BoC might be getting cold feet about further rate hikes from here.

What does all this mean for the interaction between monetary policy and economic activity in Canada? Firstly, we see inflation remaining above the BoC’s 2% target for an extended period as weaknesses across housing markets and fragilities in mortgages constrain the scope for rate hikes that are necessary to bring inflation down. Instead, we expect the BoC to prioritize near-term stability in the housing market and financial sector over a rapid return to low and stable inflation. This will also result in a weaker Canadian dollar which in turn will push up import prices. In the interim, policymakers are hoping that imbalances that have built up in the housing and mortgage markets will sort themselves out, likely in part through financial repression.[13] Secondly, contrary to the BoC’s forecasts of a soft landing, we see Canadian economic growth turning negative in 2023 as higher mortgage payments start to kick-in for the $440 billion in net new mortgages that were issued by Chartered Banks since 2017-Q1, adding to pre-existing pressures on households in the form of falling real wages and a likely uptick in unemployment.

While Alberta seems to have avoided many of the worst excesses of the housing market, these macroeconomic dynamics still hold important implications for businesses and households across the province. Ensuring that communities are appropriately prepared is an important role for public policy to fill, including through providing guidance on debt restructuring (if necessary), or offering support to entrepreneurs who see new opportunities emerging from the market adjustments that are about to take place.

[1] The Bank of England purchased some GBP 19 billion of UK government debt in order to restore stability to pension funds that incurred losses through using ‘liability-driven investment’ strategies.

[2] Bank of Canada, Monetary Policy Report (October 2022).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Other sectors showing weakness include durable manufacturing – due to higher rates and consumer preferences shifting in favour of services – and management of companies and enterprises.

[5] The Bank of Canada’s current forecast (October 2022) anticipates that inflation will fall gradually from 6.9% in 2022 to 4.1% in 2023 and 2.2% in 2024; all while maintaining positive GDP growth. This appears to be an exceptionally benign baseline forecast of a soft landing, particularly given the many risks and vulnerabilities that appear to be in play.

[6] As expressed by Milton Friedman, ‘monetary actions affect economic conditions only after a lag that is both long and variable’

[7] This is exactly the scenario that the US is seeking to avoid as policymakers recall the premature easing in the 1970s which ultimately made the task of reducing inflation much more difficult. Indeed, the BoC’s new-found dovishness puts it markedly at odds with the Federal Reserve’s indications that interest rates in the US will remain higher for longer.

[8] The Canadian household sector, with a household credit to GDP ratio of 106%, joins Switzerland (129% of GDP), Australia (118%), and Korea (105%) as the most heavily indebted in the world.

[9] Unfortunately for these borrowers, variable rates since then have increased by much more than the initial saving that they received versus a 5-year fixed rate.

[10] N.B. Please note that this data refers to Charter Banks’ issuance of mortgages. We estimate that this segment accounts for around 70% of all outstanding mortgages in Canada, with Credit Unions, Mortgage Investment Entities (MIEs), and other types of non-bank lenders accounting for the remaining 30%.

[11] Our approach to providing this illustration relies on several assumptions, including: 1) an initial amortization period of 25 years, which becomes 20 years when the loan is refinanced after 5 years; and 2) the spread between the financial markets-implied interest forecast (see Figure 1) and 5-year fixed mortgage rates is set a 200 basis points, which is within historical norms.

[12] Alberta, comparatively speaking, has seen much less of the excesses in terms of price growth and corresponding instability than other locations.

[13] The term ‘financial repression’ refers to savers earning rates less than the rate of inflation, with borrowers benefitting as their loan balances are reduced in real terms.